Distinguishing Drawing from Copying

- jesseflynn

- Sep 4, 2024

- 5 min read

By Jesse Flynn 4 September 2024

Drawing used to be a fundamental part of school curriculum taught along-side maths and english. Unfortunately, this is no longer the case. Not long ago Before a gesture drawing class I was warming up with some invented figures on my drawing board. The model arrived, upon seeing these. asked "did that come from your head," on my confirmation he replied "I didn't know that was a thing". This is one of many examples, that leads me to believe that most people have no clue of what drawing is.

Today people would generally assume drawing is to copy something with a pencil on paper. Sadly, this usually means a photograph. I therefore endeavour to distinguish drawing from copying.

As we are now well into the 21st century, we are witnessing a revival in education in the fine arts, which was very much discouraged in the 20th century. That is learning to best represent a subject from our 3D world on to a 2D surface, be it in pencil, charcoal or paint.

Learning how to represent the world around us as a means not an end. The more ease we have in representing the world outside, the more ease we have in representing the world inside. That is to communicate ideas, with the world’s oldest and most universal language: the visual language.

In the past decade many small schools have popped up around the world, mostly in America and certain art historical centers in Europe such as Florence, terming themselves ‘Ateliers’. I see this as positive and overall represents a hunger for education in this field.

However, before flying across the world and forking out tens of thousands, it is sensible to look into these schools. Weigh up their teaching methods and look under the surface. Many of these schools focus their efforts on rendering, emphasizing surface polish. But there is a wealth of useful study beneath the surface.

Many of these ateliers teach a method of copying commonly termed sight-size, where the student copies the subject at the size that it is seen. This is an exacting method which requires perfect conditions. The canvas or paper (support), must be set up right next to the subject. The size of your support will determine your distance from the subject. Once underway your viewpoint cannot change, even the slightest head movement will put everything out of line. Usually, when employing this method, the student tapes the position of their feet, the easel, their subject, the lighting and every other variable. Due to these precise conditions, it is a limiting method and not applicable to everyday life.

When the conditions are set, it’s a fairly simple procedure. A rendered picture is accomplished but the process is without much thought. It is easy to teach as there is little teaching involved. Just set the conditions and ask the student to copy the values.

The student traces horizontal lines directly from the subject to the support to set the 2D image. The verticals are set with the use of plumb bobs and visual aids such as black mirrors are used to map out the shadow shape. It is through fine rendering that the surface of the subject becomes more 3 dimensional. Of course, not every atelier relies solely on this method but it is the core instruction of many.

There is nothing wrong with this approach, however it is but one tool. To actually draw and not copy we require the whole tool belt.

To truly understand the subject you wish to represent, you must look beyond the surface and not merely copy the light reflected into your eyeballs. Of course, understanding light is important, in fact a deeper understanding of how light works opens up more possibilities, rather than just copying what you see. Understanding the form and structure of your subject: anatomy, that which is underneath the surface, allows you to modulate the light pattern to better describe form. Also playing their part are the qualities of weight, space the form takes up, the space around it, atmosphere and perspective.

In portraiture we must go beyond copying what we see to understand the skull’s anatomy. (Quick tip: the eyeball goes inside the eye socket.) Equally, we need to recognize the character, individuality, mood and most importantly humanity of our sitter.

This all being understood, we have the challenge of composing the picture in a manner that best conveys the idea, story or message we are trying to communicate. This is where an understanding of Art History makes its valuable contribution. We stand on the shoulders of masters of the past. In contemporary art, novelty is sought but to be original is to have some connection to the great work of the past, to have some conversation with our origins.

Copying is easy

Any one with 20/20 vision can perceive images with their eyeballs, all they need is the motor skills to print on paper. This can be achieved by sheer will and repetition, 500 drawings later you might have something resembling your subject. This takes patience and perseverance yes, but not brains. Copying is a useful tool, it is but one of many.

Drawing is hard

To draw is to understand. That is to stand under the masters and soak up the great wealth of knowledge accumulated over time. Drawing is thinking on paper. A network of lines, shapes and values, at first a chaotic and messy, over time these will begin to correspond with one another. We come to see the relationships and proportions. Only then, do we adjust, remove detail and progress. Eventually the chaotic mess coalesces and becomes composed thought, which conveys ideas and feelings.

Drawing can be rough and ready

The work doesn’t have to have a finely rendered surface, more important is the underlying structure. With experience, the draughtsmen’s short-hand and attitude makes its contribution.

Drawing can be diagrammatic / analytical

Explaining the unique characteristics: anatomy, mechanics, elements, movements and varied possible forms, such as those found in botanical illustration.

Drawing can be calligraphic

With particular lines, hatches and brushstrokes unique to the artist’s hand. This is why two equally skilled draughtsmen working from the same subject, in the same conditions, produce completely different results.

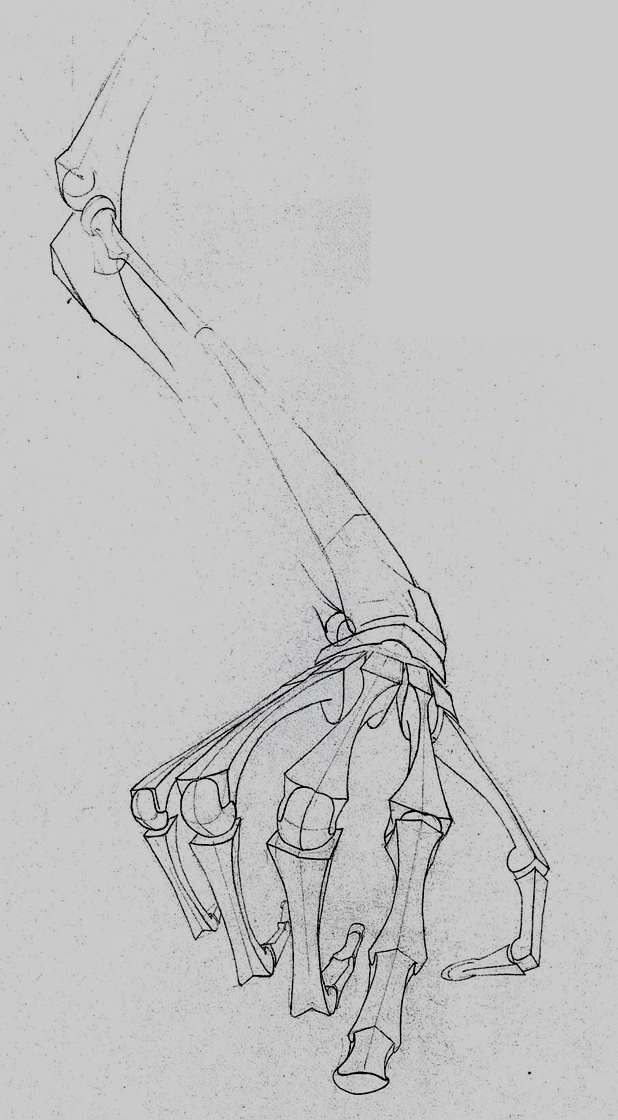

Drawing can be inventive

You can conjure images and compositions from your mind. This is where a full understanding of drawing comes in handy (ie: the complete tool box). A photograph may seem like an aid but it is actually a constraint to our imagination.

It's not just the photo that is constraining. The model and the confines of the studio can be. Any pose is contrived and held over time will lose its initial vitality. In reality no one holds perfectly still.

That's why the best life drawing is done in real life, in cafe's, parks and waiting for the bus. Don't ask permission, just observe the true gestures of nature. This is food for imagination.

With the ‘tool box’ you can do a good deal without a model. We learn from the model in order to draw from our mind. This is the basis for many great Renaissance works.

Drawing embraces uncertainty

We need to be able to draw in any conditions, to be open to changes, because real life changes constantly. And this is a blessing not a curse. We don’t need to take snap shots; we have invented devices for that. Embrace the changes, the movement, the mood, the light. Learn where to chase the pose and not to chase.

A drawing composed with time, can be viewed over time, not just scrolled past like the atelier pictures on my Instagram feed.

Comments